By Terri Somers

Senior Manager, Global PR and StoryLab

Expedition team members wearing metallurgic, heat-resistant suits look for newly deposited minerals and the first signs of life inside fresh lava tubes. (Robbie Shone, National Geographic)

Expedition team members wearing metallurgic, heat-resistant suits look for newly deposited minerals and the first signs of life inside fresh lava tubes. (Robbie Shone, National Geographic)

This first-of-its-kind expedition, funded by the National Geographic Society, aimed to uncover how life strategically uses subterranean environments to spread around the Earth, said Francesco Sauro, the Italian geologist and speleologist who led the expedition.

The team’s research would also provide important clues to other volcanic environments that cannot be explored, such as Mars, said Sauro, who helps train European Space Agency and NASA astronauts for planetary exploration.

Penelope Boston, former director of NASA’s Astrobiology Institute, who now helps develop new research and mission concepts, sees great value in the investigation of lava tubes because they may be found on other bodies in the solar system. “I think that designating places around the world where we have this ability to see an early history of microbial colonization from the get-go is something that deserves worldwide attention,” Boston told Smithsonian Magazine.

Real life in real time

Miltenburg, then an applications scientist for analytical instruments working in the Netherlands, was tasked to transport, set up, and monitor the Thermo Scientific Phenom XL G2, a portable scanning electron microscope (SEM) that Sauro said was crucial to the mission.

The SEM, which utilizes an electron beam rather than light, can show structures at the nanometer scale—far beyond the resolving power of traditional light microscopes. This capability allowed scientists to examine microscopic samples of highly unstable minerals and micro-organisms just minutes after they were scooped from cave walls.

In addition to providing high-resolution, detailed images of the tubes’ contents, the SEM uses electron dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), which analyzes the x-rays emitted by the electrons in the samples to determine their composition, Miltenburg said.

Expedition team members in heat-resistant suits climb into a fresh lava tube in southern Iceland in search of newly deposited minerals and the first microscopic signs of life. (Robbie Shone, National Geographic)

Expedition team members in heat-resistant suits climb into a fresh lava tube in southern Iceland in search of newly deposited minerals and the first microscopic signs of life. (Robbie Shone, National Geographic)

Without the SEM on site, samples would likely need to be placed into vacuum tubes and then prepared for shipping to a lab on another continent, where a larger, stationary SEM would be available.

That is an impractical alternative because Sauro said that most of the samples taken from the tubes on Fagradalsfjall are so unstable that they immediately change and degrade when exposed to changes in temperature and humidity. Some crumbled, some dissolved into a brine, and others crystallized when removed from the tubes, he said.

“Having the SEM on site allowed us to observe the metastable minerals in their original crystalline form and (over time) while they were changing in the vacuum of the SEM columns,” Sauro said. “Also, it allowed us to identify which samples featured microbial colonies.”

Thermo Fisher Scientific’s Rogier Miltenburg, center, demonstrates the features of the company’s portable SEM to expedition team members. (Vittorio Crobu, La Venta)

Thermo Fisher Scientific’s Rogier Miltenburg, center, demonstrates the features of the company’s portable SEM to expedition team members. (Vittorio Crobu, La Venta)

Volcanos are often in locations that make them almost impossible to reach, and the terrain is often treacherous.

Fagradalsfjall, however, is a cluster of ridges on a plateau conveniently located about 25 miles from the Reykjavik airport. And the volcano has been monitored very well by Veðurstofa Íslands, Iceland’s meteorological institute, which tracks the 30 active volcanos on the tiny island nation.

Also helpful, the Fagradasfjall eruption was effusive, with low-viscosity lava flowing from fissures and cracks, rather than exploding into the air with rock and ash.

The first streams of lava appeared in mid-March 2021. Icelanders had plenty of warning, thanks to the more than 50,000 earthquakes that were recorded during the preceding year.

Mount Fagradalsfjall in southern Iceland first erupted in March 2021, after eight centuries of dormancy. It quickly became a tourist attraction because the terrain is more accessible than many volcanos, the lava flow was effusive, rather than explosive, and it is located only 30 miles from Reykjavik, the nation's capitol, and 25 miles from the international airport. (Shutterstock)

Mount Fagradalsfjall in southern Iceland first erupted in March 2021, after eight centuries of dormancy. It quickly became a tourist attraction because the terrain is more accessible than many volcanos, the lava flow was effusive, rather than explosive, and it is located only 30 miles from Reykjavik, the nation's capitol, and 25 miles from the international airport. (Shutterstock)

In the first week of the six-month eruption, thousands of tourists flocked to the site, taking photographs and recording video that was widely shared on the Internet and would come in very handy in planning the expedition. Sauro was there, too, to take an early look at the terrain and scan for the beginning signs of lava tubes.

When first formed, the temperature of the tubes is about 1,200 °C (2,190 °F), Sauro said. These extreme temperatures, create a completely sterile environment. Only when it cools to about 100 °C (212°F), does life begin to form, transported in by the wind, rain, and mist.

Multiple visits to monitor temperatures and scan for tube formations are necessary. In only one other erupting volcano, Italy’s Mt. Etna in 1994, had researchers managed to enter fresh lava tubes and find metastable minerals, meaning they maintain stability only at high temperatures. At Fagradalsfjall, Sauro’s team also sought to capture samples of the first microbic life forms moving into the tubes and colonizing, he said.

Expedition team members carefully make their way across a cooled lava flow. (Robbie Shone, National Geographic)

Expedition team members carefully make their way across a cooled lava flow. (Robbie Shone, National Geographic)

In Iceland, the tubes were generally three-to-four meters (10-13 feet) high and two-to-three meters (6-10 feet) wide, allowing the explorers to walk rather than crawl, he said.

But it’s treacherous work requiring great care and athleticism. It is not an adventure for the claustrophobic or those with joint issues.

The tube walls sometimes glow from retained heat – one team member recorded 410 °C (770 °F) on one wall. They can also be thin and susceptible to collapse from contact, cooling, noise, or tremors from deep within the earth.

Sauro and team continually monitored Fagradalsfjall, using photographs and video they found online, and photos taken by the University of Iceland’s Nordic Volcanological Center and the Icelandic Institute of Natural History, to map the lava field and pinpoint tube entrances. Sauro also twice visited the volcano, looking for lava tubes and recording temperatures near their entrances.

About one year after the eruption began, the team found the temperatures around several tube openings had dropped to 250-300 °C (482-582 °F).

While that is the equivalent of a commercial pizza oven, it was finally cool enough for human exploration using special equipment, including metallurgist suits that withstand high temperatures, gas masks to protect against poisonous gases, and portable tanks of compressed air cool enough for human lungs.

Expedition leader Francesco Sauro, president of the Association La Venta, an organization focused on geographical exploration in extreme environments, emerges from a dangerously hot lava tube. (Robbie Shone, National Geographic)

Expedition leader Francesco Sauro, president of the Association La Venta, an organization focused on geographical exploration in extreme environments, emerges from a dangerously hot lava tube. (Robbie Shone, National Geographic)

Setting Up Basecamp

Climbing the volcano’s southern flank, where promising lava tubes had been observed by Sauro, meant sticking to a path carefully plotted by drones equipped with thermal cameras, which allowed the creation of a three-dimensional model of the lava flow everyone needed to avoid walking on.

“You could feel the heat coming off the rocks and see the refraction of the heat,” Miltenburg said. “It’s an eerie environment, like walking on another planet.”

As he climbed, expedition members talked about how one wrong step could send you crashing through dried lava and plummeting to great depths. There was also chatter about how, on a previous expedition at this same volcano, scientists were forced to run out of lava tubes when the government agency monitoring the volcano contacted them and warned an eruption was imminent.

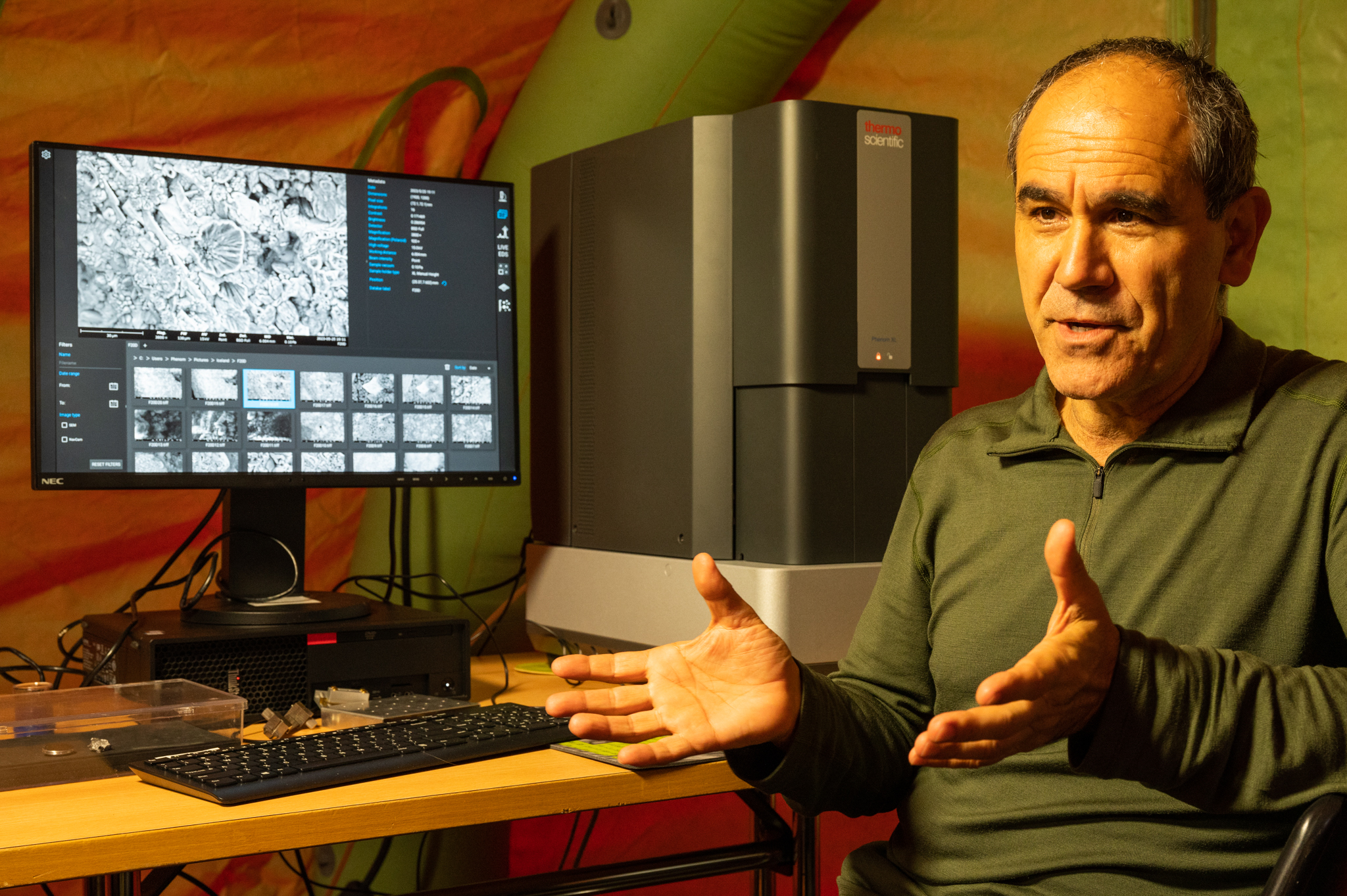

Expedition team member Bogdan Onac, a mineralogist from the University of Southern Florida, discusses images of samples taken from the fresh lava tubes using the Thermo Scientific Phenom XL G2, a portable scanning electron microscope, pictured in background. (Robbie Shone, National Geographic)

Expedition team member Bogdan Onac, a mineralogist from the University of Southern Florida, discusses images of samples taken from the fresh lava tubes using the Thermo Scientific Phenom XL G2, a portable scanning electron microscope, pictured in background. (Robbie Shone, National Geographic)

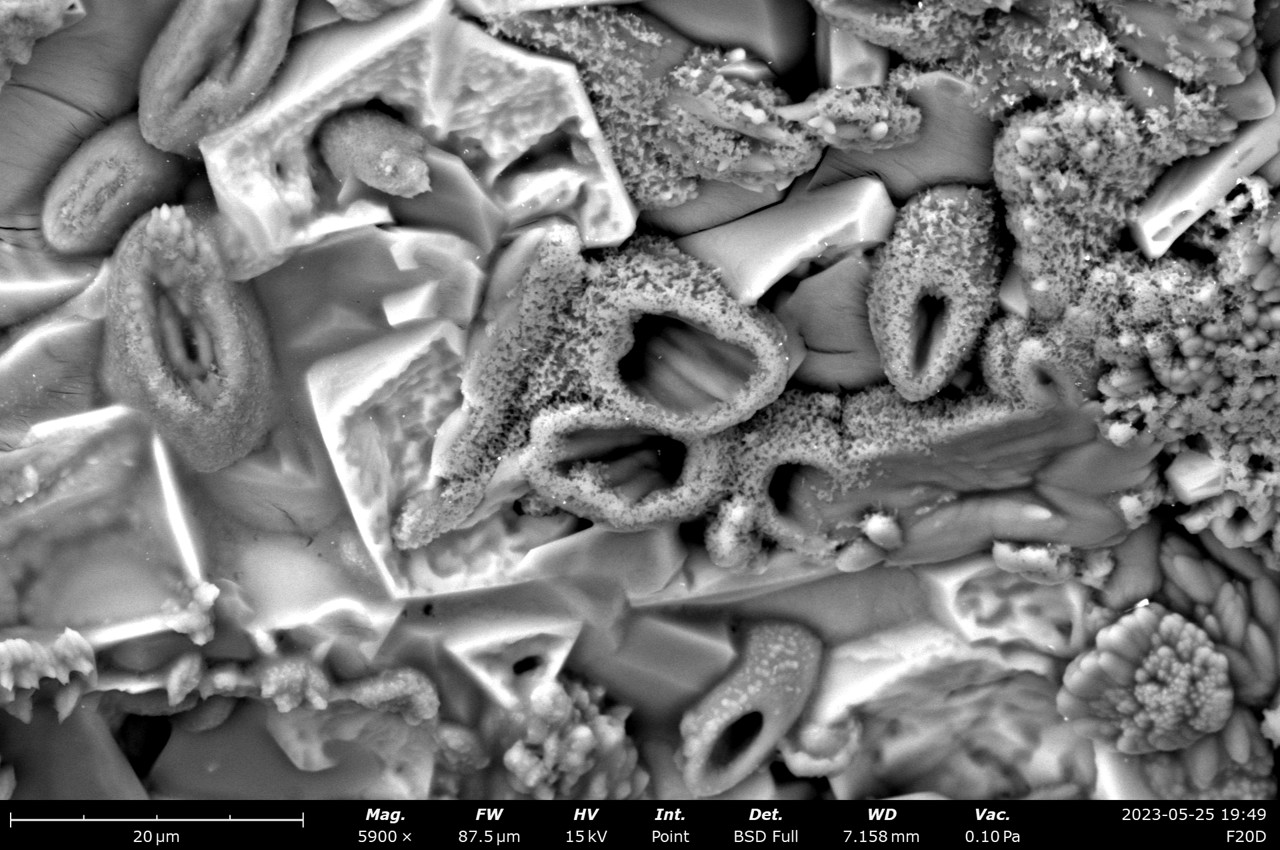

They put a prepared slide with pieces of the sample under the SEM and “honestly, it was the most beautiful sample I had ever seen,” Miltenburg said, smiling. “It was really an amazing image of seashell shapes and pointy needle structures.

Everyone just crowded around and said “WOW,” as time seemed to freeze for a few seconds, he recalled.

Then the scientific thinking clicked into gear. The tent buzzed with the scientists’ discussion of what they saw.

An image captured by Thermo Fisher’s portable SEM shows a mineral sample taken from the lava tubes at 5,900X magnification. (Rogier Miltenburg, Thermo Fisher Scientific)

An image captured by Thermo Fisher’s portable SEM shows a mineral sample taken from the lava tubes at 5,900X magnification. (Rogier Miltenburg, Thermo Fisher Scientific)

“Fifteen people were standing around the microscope looking at the image and discussing the data, which was the amazingly cool part: collaboration of different expertise and discussion of science was happening while on the expedition,” rather than months later, in a conference room or Zoom meeting, Miltenburg said.

Having the SEM on site also meant the crew needed to remove less material from the tubes, he said. Subsequent gatherings around the SEM were fascinating and exhilarating, he said.

“You’d have five people, all with different areas of expertise, talking about what they thought they were seeing, and others saying they had no clue,” he said. “Another time, someone said they were looking at something that they thought had never been found (in a cave) before. The excitement was palpable. You could see, hear, and feel how they loved their job and what they were getting to do.”

A mineral sample on the wall of a fresh lava tube. (Vittorio Crobu, La Venta)

A mineral sample on the wall of a fresh lava tube. (Vittorio Crobu, La Venta)

When temperatures dipped below 100 °C (212 °F), the group saw what it considered to be the most important mineral formations, Sauro said. At that temperature, humidity develops and reacts with sulfur gasses and metals on the wall, “resulting in very strange minerals,” he said.

As the team scoured the tubes, they used a bioluminometer to find areas of luminescence, indicative of chemical reactions that take place when life is present. In three locations, where the temperature had fallen below 67 °C (152.6 °F), “the point when water stops rapidly evaporating,” scientists found what they hoped was microbial life.

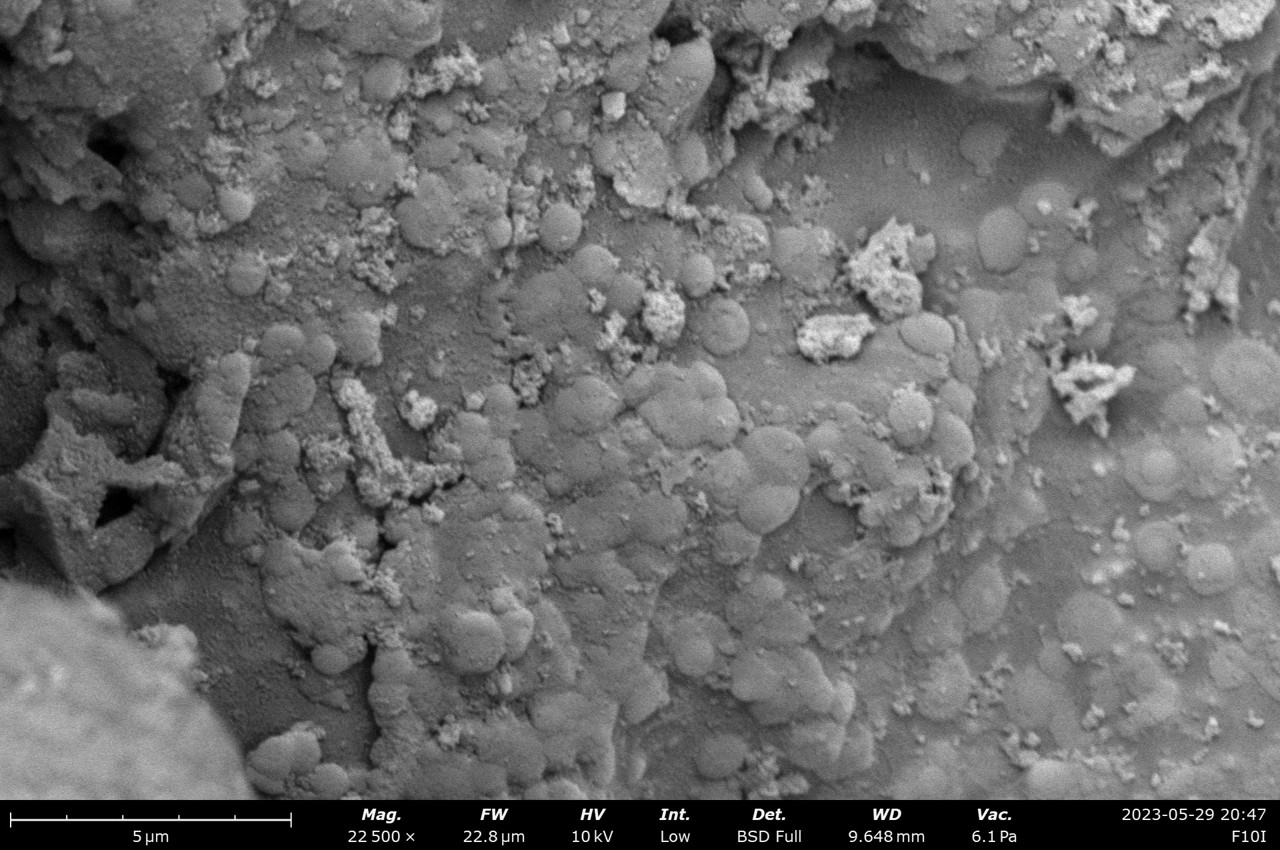

Thermo Fisher’s portable SEM enables highly magnified images of bacteria samples taken from the lava tubes. (Rogier Miltenburg, Thermo Fisher Scientific)

Thermo Fisher’s portable SEM enables highly magnified images of bacteria samples taken from the lava tubes. (Rogier Miltenburg, Thermo Fisher Scientific)

Through the magnification enabled by Thermo Fisher’s SEM, they could see clusters of coccoid-shaped bacteria, embedded in a glue-like matrix…or biofilm, Sauro said.

In the sunless environment of the tubes, the bacteria use the water in the minerals and chemical reactions, such as the oxidation of sulfur, iron, and copper, to create energy and proliferate. The carbon from the bacteria’s growth then attracts other bacteria. The bacteria analyzed there is most often found in soil and salty environments, Sauro said.

“These bacteria represent the first colonizers of the extreme environment, showing that life quickly proliferates when temperature allows (only 18 months after the eruption end), with implication for astrobiology,” Sauro wrote in his final report to National Geographic.

The discoveries unearthed by Sauro and his team of explorers and scientists has earned them recognition and admiration beyond NASA scientists.

.JPG) The expedition team erected a tent on the volcano to serve as their basecamp where they gathered each day to analyze samples. (Rogier Miltenburg, Thermo Fisher Scientific)

The expedition team erected a tent on the volcano to serve as their basecamp where they gathered each day to analyze samples. (Rogier Miltenburg, Thermo Fisher Scientific)

Back at work now in Eindhoven, with almost a year to reflect on his experience, Miltenburg said that what sticks with him most are the stories the researchers shared about their adventures and the work during their downtime on the side of Mount Fagradalsfjall.

“You don’t end up in such a place if you’re not a little bit whacky,” he said laughing.

“Of course, not in a bad way: they’re all really driven by their passion and that is a really nice environment to be in. I was thrilled to play a small role through my job, helping provide technology that allowed the expedition to push the boundaries.”