Episode 029

Why Tick Season Isn’t the Only Time to Focus on Alpha-Gal Syndrome with Dr. Scott Commins

-

Summary

-

Episode Resources

-

Transcript

-

Related Episodes

Episode summary

In partnership with Food Allergy Research & Education (FARE), Gary Falcetano discusses the unique challenges of diagnosing and managing alpha-Gal syndrome (AGS), a red meat allergy triggered by tick bites with Dr. Scott Commins, a leading expert in AGS and distinguished professor at the university of North Carolina. They explore the distinct nature of alpha-Gal as a carbohydrate allergen, the prolonged journey to diagnosis, and the syndrome's expanding geographic prevalence. Key topics include the delayed onset of symptoms, the role of fatty meats in severe reactions, and the presence of alpha-Gal in medications. Gain valuable insights into effective management strategies and future treatment possibilities, equipping healthcare providers with the knowledge to better support patients with AGS.

Guest spotlight

Dr. Scott Commins

Dr. Scott Commins is the William J. Yount, MD Distinguished Professor at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he is a member of the UNC Food Allergy Initiative, the Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases, and the Southeastern Center of Excellence for Vector Borne Diseases. Dr. Commins received his MD and PhD (Biochemistry & Molecular Biology) from the Medical University of South Carolina. Following a residency in Internal Medicine, Scott completed a fellowship in Allergy and Clinical Immunology at the University of Virginia. He is an author for UpToDate and serves as the Chief Editor for the Drug, Venom & Anaphylaxis section of Frontiers. Dr. Commins is the immediate past-president of the Southeastern Asthma, Allergy, and Immunology Society, and was a member of the Congressionally appointed Tick-Borne Disease Working Group (2018-2020), where he was co-chair of the Alpha-gal syndrome and public comment subcommittee.

Episode resources

Find the resources mentioned in this episode

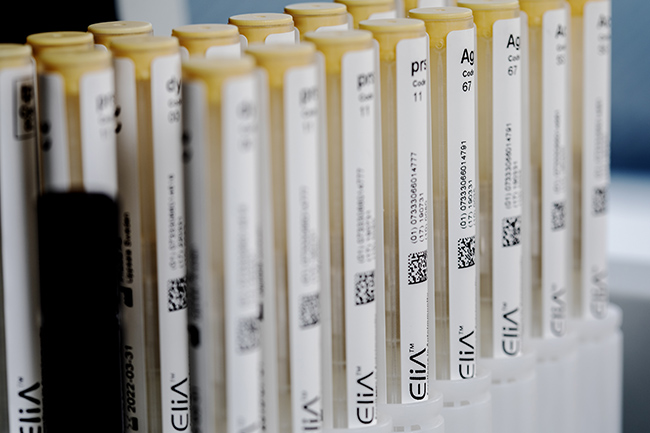

Lab Ordering Guide

Looking for allergy diagnostic codes from the labs you already use?

Episode transcript

Time stamps

1:23 - Dr. Golden's Background in Insect Allergy Research

1:47 - Dr. Commins Background

3:15 - Alpha-Gal Syndrome Overview

5:43 - Spectrum of Alpha-Gal Symptoms

7:49 - Patient Journey for Alpha-Gal

11:31 - Geographic Distribution of Alpha-Gal

14:07 - Early Symptoms of Alpha-Gal

16:01 - Diagnosing Alpha-Gal Syndrome

18:51 - Global Prevalence of Alpha-Gal

21:20 - Alpha-Gal Hotspots in the US

25:35 - Increasing Awareness Among Clinicians

29:26 - Alpha-Gal in Children

35:49 - Delayed vs. Immediate Symptoms

39:36 - Alpha-Gal in Foods and Medications

43:26 - Cofactors Affecting Alpha-Gal Reactions

45:05 - Resolution of Alpha-Gal Sensitivity

46:32 - Alpha-Gal as a Top Food Allergen

47:47 - Potential Future Treatments

48:44 - Connections to Other Conditions

50:11 - Interpreting Alpha-Gal Test Results

Announcer:

ImmunoCAST is brought to you by Thermo Fisher Scientific, creators of ImmunoCAP™ Specific IgE diagnostics and Phadia™ Laboratory Systems.

Gary Falcetano (00:13):

I'm Gary Falcetano, a licensed and board certified PA with over 12 years experience

Luke Lemons (00:17):

In allergy and immunology. And I'm Luke Lemons with over six years experience writing for healthcare providers and educating on allergies, you're listening to cast your source for medically and scientifically backed allergy insights. On this episode of Immuno Cast, we're going to be doing something a little bit different In partnership with fair, the Food Allergy Research and Education Organization, Gary had presented a webinar on AlphaGo syndrome or red meat allergy to clinicians and patients alike. He does this with co-host Dr. Scott Cummins, who is a distinguished professor from the University of North Carolina and a world leading expert in AlphaGo. In fact, they were a member of the congressionally appointed Tick-Borne Disease working group from 2018 to 2020 where he was a co-chair of the Alpha Gal Syndrome and public comment subcommittees, he knows a lot about Alpha-Gal. I think him and Gary do a great job in going into some tips and tricks around diagnosing Alpha Gal syndrome, managing patients, and also just a background on this disease state.

Luke Lemons (01:19):

They are presenting a webinar, so they will be speaking to slides that of course you can't see, but they do go through exactly what's on the slides in instances where they're not clear. I'm going to pop in and just kind of explain a little bit of what they're talking to. And in this episode's description, you can actually find a link to watch this webinar if you feel so inclined. The audio that we're going to start with and that you're about to hear is Dr. Scott Cummins introducing himself to the viewers. I hope you enjoy this episode. Let's jump in.

Dr. Scott Cummins (01:48):

Yeah, I appreciate the opportunity to be here and talk about Alpha Gal syndrome, which is near and dear to my heart. I was, as you might say, kind of boots on the ground when all this developed in Tom Platz Mills' lab. He was the senior author and I was the first author on the 2009 paper that basically described AlphaGo syndrome in the US and it was a hard sell at the moment, right, to think about changing the paradigm of food allergy. But a little bit about me, I'm married to my bride, Jenny and have two children both in college now. I got into allergy actually because I really wanted to see kiddos. I'm trained as an internist but enjoyed seeing children and really wanted to be able to have a presence both in the lab and in the clinic. And it turns out I don't really like the hospital, so allergy was a perfect fit and I ended up with Tom Platz Mills at the University of Virginia for fellowship. I think we had no idea in 2009 that the description of two dozen people would turn into something that we've been working on now for almost 25 years. So that's a little bit about me. I'm at UNC and really enjoy being at Carolina and I'm quite proud to be the William Yt distinguished professor. He was a staple and a pillar in the UNC allergy rheumatology community.

Gary Falcetano (03:16):

Quite deserved in. Yeah, you're a great representative for sure. As we move in, again, I said we weren't going to do a strong didactic presentation. I think especially probably most people tuning in have heard of Alpha Gal and are somewhat familiar. Let's just spend a few minutes talking about kind of what it is. Again, really briefly, maybe we can discuss those separate episodes or instances that really led to its identification as an allergen and as a really unique syndrome. So galactose alpha one three galactose, it's oligosaccharide a sugar molecule. Why is that different from most of the allergies that we see today?

Dr. Scott Cummins (03:57):

It's a foundational point, which is basically everything we knew about allergy food allergy as well was predicated on the fact that 99% of allergens were proteins, our proteins. And so AlphaGo being a sugar is unique. There have been in the past descriptions of carbohydrate or sugar-based allergens, but they're generally considered to be fairly weak and cross reactive. So AlphaGo was unique in two ways to start with, which was it wasn't a protein and it certainly did not appear to be a weak allergen.

Gary Falcetano (04:39):

Yeah, exactly. Because some of those other sugar molecules like cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants, we see responses antibody responses to them, but we don't typically see clinical symptoms. Correct.

Dr. Scott Cummins (04:51):

Yeah, that's exactly right. And it can get confusing, right? You can be allergic so to speak, or sensitized to a carbohydrate that may be on grass pollen and it cross reacts with peanut and it gets very complicated. But you're correct. In general, the thought prior to the description of Alpha-Gal syndrome was that carbohydrates were kind of distractors in the allergy space.

Gary Falcetano (05:15):

Yeah, exactly. So when we talk about Alpha-Gal syndrome, it really is a spectrum, right of presentations, I think, and I think that's really, there's a few things that make it challenging. One part is certainly the delayed diagnosis or the delayed symptoms part. The other part is that so many people have so many different types of expression, right? If they have this allergy, maybe just talk again a little bit about what we commonly see with Al Alpha-Gal syndrome.

Dr. Scott Cummins (05:43):

Sure. Not very different from the typical peanut milk or egg allergies where you might have a patient who is okay with an allergen or a food that would be processed in or may contain, whereas you would have other patients who would have to strictly avoid that kind of labeling. That certainly seems to be true in the AlphaGo syndrome space as well, where some patients or folks affected are incredibly sensitive and even have trouble with fme based reactions, whereas we have other patients who are okay with dairy, which we know has Alpha-Gal as well. So there's a wide variety of expression, so to speak, of the symptoms and sensitivities related to AlphaGo syndrome.

Gary Falcetano (06:36):

So when we think about AlphaGo syndrome and the patient journey, how it's acquired, as I said, I think most people that are tuning in today know that this is the tick being the vector for the sensitization for AlphaGo syndrome. If you think about all of the patients that you've seen, would you say this is the typical journey that we see for patients and when this isn't the journey, what are some of the atypical presentations you see as well?

Luke Lemons (07:09):

Hi, Luke here popping in to really quickly explain this slide. The slide that Gary's speaking to here outlines the patient journey for Alpha Gal. There's four checkpoints in this journey. The first being a tick that is a carrier, the second being the tick actually biting the patient. And then between the second and third checkpoint, there's about a one to three month period in which IgE to alpha gout increases the third checkpoint, then being ingestion of red meat, and then another time gap of about two to six hours, which then leads to the final checkpoint reaction. Really this slide seems to be outlining that there are gaps in time between these events in AlphaGo syndrome.

Dr. Scott Cummins (07:50):

The tick bite seems to be front and center for sensitization as you said, and we'll talk about that in a bit. We have, I would say, convincing evidence that the tick bite and in the US that seems to be the lone star tick, but the tick bite really appears to drive the development of the allergy. And this seems to be a process shown here where after a tick bite, we are still working on trying to understand the risk in some of this, is the risk from the tick or is the risk from the host and how do we quantify that? But post tick bite, it probably takes, at least in the initial stages, when someone begins to develop alpha-gal syndrome on the order of months, I think appropriately listed here, we often say six to eight weeks, but one to three months fits in there.

Dr. Scott Cummins (08:43):

And some of that is to develop an IgE response, just the B-cell machinery that's needed to create the IgE. Then you populate your allergy cells with the alpha-gal IgE and then you have to eat the wrong food or the wrong food being the allergen containing food. So in that setting of Alpha-Gal, that would be basically non-human, non primate mammalian meat. I think more easily we would say red meat. So then you have to eat beef, pork, lamb, venison, goat, whatever, some sort of red meat. And then unlike other food allergies, it takes two to six hours for symptoms to develop. That can be hives, swelling, itching, redness. Increasingly we're finding that it could also be just gastrointestinal distress. I don't mean just in that it doesn't hurt or it's not painful. It does hurt and it can be quite painful, but it doesn't always have to be this constellation of symptoms that would drive people to an allergist.

Dr. Scott Cummins (09:49):

And because it's delayed, often we find that in keeping with that the diagnosis is delayed because the paradigm of food allergy is that it happens at the restaurant, right? AlphaGo syndrome typically happens at home because your hours after the meal. And so when you present to the ED in the middle of the night with hives and gastrointestinal distress, we've had patients say, one of the things they told me was it can't be a food allergy because I ate six hours ago. So it's tough to sometimes get the diagnosis and because of that raising awareness is important just like what we're doing today. So that's the typical approach or journey, if you will. And for many years, the average time from initial reaction to diagnosis was pushing seven years, which just is mind blowing. But I think because of awareness, we're getting the word out and we're getting to the point where we're really reducing that time to diagnosis number and hopefully that becomes an atypical journey and that the much more typical journey becomes a faster time to diagnosis and then avoiding the culprit foods.

Gary Falcetano (11:07):

So I think we're going to have some questions in just a minute, but I think, and I'm kind of getting ahead of us, but we'll also talk about the geographic distribution of Alpha-Gal patients and throughout the country, throughout the world. But while we're looking at this picture of the lone star tick, we know it's not just the lone star tick. So maybe just speak to that quickly and then we'll move into some questions.

Dr. Scott Cummins (11:31):

Yes. In the US we think we believe that the lone star tick is the primary driver or culprit behind AlphaGo syndrome, but we know this is a global phenomenon and in locations outside of the US, there really are not lone star tick population. So we know that even though the lone star tick do it, it is not the only tick that can do this.

Gary Falcetano (11:56):

And I think you know what, we'll save maybe some of those other potential vectors for a little bit later. But as I said, questions have really been probably the most popular of these webinars. Our first question, and I think you discussed some of this already, what are the early symptoms of AlphaGo syndrome and how long does the tick need to be attached? Because we know with Lyme disease, we typically hear 24 hours is required for attachment to transmit the organism, but what do we think about AlphaGo?

Dr. Scott Cummins (12:28):

So to answer the back portion of that, first, it's a fascinating question. One we're certainly working on, and I will tell you difficult for us to do that experiment. We don't ask people to leave their ticks on. So what we tend to think is that if the tick has been attached long enough to give someone a red itchy spot that is inflamed and perhaps reactive, then that unfortunately is probably long enough for the tick bite to drive the allergic response. And that seems as though it can happen probably in the order of 15 or 20 minutes, maybe one to two hours. But certainly as you mentioned, very different from what we see in the infectious diseases world related to transmission of an organism. This allergy unfortunately happens fast. And so part of that, we may talk about this too, but tick checks are important, but prevention, tick bite prevention then becomes key because of this.

Gary Falcetano (13:29):

Yeah, no, I think that makes a lot of sense. Certainly with Lyme disease, we can do those tick checks and get them off in a few hours after going for a hike, but here the right insect repellents and clothing and we know all those kind of recommendations for preventing the actual tick bite to begin with. Maybe quickly talk about, I mean you discussed rash urticaria, you discussed GI symptoms and potentially, I mean we used to call this midnight anaphylaxis, right? Because that's where we started seeing these cases of true severe reactions, but it really is a spectrum. And so I think to answer the early symptoms, are there any others that you can think of that we haven't mentioned so far?

Dr. Scott Cummins (14:08):

Yeah, I think it's important to think about the early symptoms. One thing that we haven't talked about that we hear a fair amount is Palmer erythema. So redness and itching of the palms is one of the very early symptoms that many patients report. It doesn't have a call name or a named sign, so to speak in the medical speak, but it is quite common. Sometimes people will say the same thing about the soles of their feet. My sense is it's just highly vascularized. And so that becomes an early sign and symptom. Then often there's a progression from that itchy redness of the hands to itching all over, perhaps flushing of the face hives, some gastrointestinal upset or distress. And then from there, some people will have respiratory trouble breathing, chest or throat tightness, and others may even have kind of dizziness, lightheadedness that may be associated with a low blood pressure. So we see the gamut basically from some early itching all the way through to anaphylaxis that should really be treated with epinephrine.

Gary Falcetano (15:23):

Yeah, exactly. I've heard some descriptions from patients that sites of the previous tick bite will also begin to itch during their reaction when they've ingested the mammalian meats. Have you seen that as well?

Dr. Scott Cummins (15:36):

Yes. That's a good pearl to bring out that it's almost as if there's some recall there where you're absolutely correct. Patients will say that the site of the prior bite, if it's been recent in particular, that that place will begin to itch as one of their initial spots. So yes, I appreciate you bringing that out.

Gary Falcetano (15:53):

So pretty straightforward. The next question, although allergy diagnosis is never completely straightforward, right? How do we diagnose Alpha Gal syndrome?

Dr. Scott Cummins (16:01):

So technically Alpha Gal syndrome really needs two components to be diagnosed. One is the history. What are your symptoms? Is there an association of an exposure that contains AlphaGo and some symptoms? So that's one thing. The second is basically a blood test, right? This is in some ways why we're here. The typical skin test that you think about coming from an allergist office actually don't work that well. When it comes to diagnosing AlphaGo syndrome, we really prefer the blood test. There's a specific immuno cap that is basically the one that we like to use to identify AlphaGo specific IgE. So it's a two-pronged diagnosis. The clinical history and the AlphaGo IgE specific blood test,

Gary Falcetano (16:55):

And I think it's important, right to speak to these allergy tests are not screening tests, so we don't want to go out and just test everyone to see if they may have it right. I think we base our testing on symptoms and a potential pretest probability that you may actually have AlphaGo syndrome.

Dr. Scott Cummins (17:11):

No, it's true. We almost teach our allergy trainees that you use the testing to basically confirm your clinical suspicion, right? So you should be suspecting based on talking to the patient, I think you may have AlphaGo syndrome. I'm going to run the test. You're absolutely correct that IgE testing in general is not great for screening and Alpha Gal IgE testing in particular is a bad screening test because in certain geographic regions there may be a fairly sizable rural population, and if they're getting tick bites, we have found anywhere from 20 to 30% of that tick bitten population who eat red meat absolutely fine, could still test positive. So bad screening tests, great. Confirmatory test.

Gary Falcetano (18:04):

Exactly. And I think that's really what we need to follow with any type of allergy, but especially with food allergy and Alpha-Gal. So let's talk about that distribution. And we know that Alpha-Gal has been identified, I believe, on every continent in the world except Antarctica. Has that changed or we still, we haven't found any AlphaGo in Antarctica, correct?

Dr. Scott Cummins (18:29):

Right. I think we still lack Antarctica as adding to the AlphaGo syndrome family,

Gary Falcetano (18:35):

But we know that, as you said, we don't have the lone star tick in some of these other locations in these other geographies, and it's not just from people being bitten in the US and relocating there. What do we think are the vectors, some of the vectors in other parts of the world?

Dr. Scott Cummins (18:51):

It appears that ticks remain the primary vector. I think it's fair to say in Alpha-Gal syndrome across the world. What's interesting to me is that in each of these areas that we have highlighted, there are different ticks really, but there are tick populations associated with the places where people throughout the globe are showing up with alpha-gal syndrome. So Sweden for example, has Exodus in Australia, they have ex's ho cyclists, and in Panama it was Ambry Cassis. So there are these different tick populations throughout the world that are associated with AlphaGo syndrome. Now, South Africa creates perhaps a different wrinkle. There are ticks in South Africa, but this is largely the work of Mike Levin who's at Cape Town University and showing that there may be actually a parasite perhaps associated more closely with AlphaGo syndrome developing in some of the South African population. So we're certainly paying attention to other vectors that may be associated with AlphaGo syndrome. Ticks remain the top on our list, but we're certainly aware that there are, and we suspect we'll find additional vectors.

Gary Falcetano (20:16):

And I think when we were back to the whole screening discussion, having that high index of suspicion and asking the correct questions as to you may be someone who in Alaska where I guess we really haven't seen many cases, but maybe they spent a few months in the southeast or went on vacation in a tick endemic area. So I think it's important for clinicians to be aware that we have highly mobile populations right now as well. But speaking of prevalences, we've seen numbers as high as, and you said where we see sensitizations as high as 10% in some of the geographies. And what do you think about that? And also about the, I think we have some future questions on this, but increasing prevalence of this syndrome.

Dr. Scott Cummins (21:03):

Yeah, there probably are true hotspots for a GS, and when we think about that in 2023, there was a large sero survey from one

Gary Falcetano (21:16):

Of the, lemme move to that, actually, I'll move to that slide so you can speak to it.

Luke Lemons (21:20):

Yeah, perfect. Hi, Luke here. Just popping in. The slide that Gary is talking to is of the United States, and it's a heat map showing per 1 million population per year, what is the number of suspected cases of AlphaGo syndrome? So we see really around Kansas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky, there's a giant splotch on this map that shows that there is a high number of alpha gal cases here. There's also a high number around the border of North Carolina and Virginia with Virginia having a majority of those. Those are the most concentrated areas that you see on this map with Alpha-Gal syndrome, with a gradient of those suspected cases decreasing as you move farther away from them. Looking west of Kansas, there is very little suspected alpha-gal cases per 1 million population per year. We do see up north, however, in the Minnesota region, especially at the very north part of Minnesota, that there seems to be some AlphaGo cases popping up as

Dr. Scott Cummins (22:24):

Well. It's kind of a sliver of blue, dark blue, but if you look out where Long Island is, Suffolk County, long Island, 4% of all the AlphaGo positive tests came from Suffolk County, long Island. So we know that there are these hotspots, and the problem is also in the hotspots. There probably are many people who test positive but have no clinical symptoms. So we have to remain aware of that. And I think to your point earlier, educating our healthcare providers that just because you live in Seattle, your patient may travel. So we need you to be aware of AlphaGo syndrome, aware of how it presents and be able to test for it, because just being dialed into the ticks in your local area is really not sufficient in terms of trying to diagnose AlphaGo syndrome and put the history together for the patient.

Gary Falcetano (23:25):

And we've seen prevalence increasing, especially in some of these kind of outlying areas, more northern areas. I saw something recently, Martha's Vineyard in 2020 had two patients diagnosed or who tested positive for AlphaGo, and in 2024 there were 150 and this small isolated island right off the coast of Massachusetts. I'm sure some of this is related to increased awareness and higher indexes of suspicion, but what role do you think the gradual warming rate of our climate is playing in this?

Dr. Scott Cummins (23:58):

I think there's probably a significant role, as you said, just beyond awareness. And part of what we really suspect here is that the white-tailed deer population, which is the largest driver of moving the tick population around the white-tailed deer population has expanded. And from everything we've been told moving into new geographic territories, expanding kind of west, which we see alpha gal syndrome right into northwest Arkansas where it's been, but now certainly into Oklahoma, Nebraska, and you see on the map some of the darker blue areas up around the Great Lakes, we're now having white-tailed deer there. So we think the deer are really pushing the ticks into new locations and unfortunately that's putting more and more people at risk for developing AlphaGo syndrome. So what we used to think as perhaps a southeastern allergy really has expanded, especially into the Northeast with the story on Long Island and Martha's Vineyard, as you mentioned. We're hearing a lot about that as well. Apparently they have quite a dense deer population and a tick population there. But then also now this movement westward, which in large part we believe is due to the migrating deer,

Gary Falcetano (25:27):

And there's even a hotspot in northern Minnesota where it's really not well explained on whether it's a vector or not. Up there,

Dr. Scott Cummins (25:36):

You're correct. I think the entomologists would have told us we don't really have lone star ticks in the northern part of Minnesota, so it remains to be seen perhaps do we have now evidence of another vector in the US that is part of the Alpha G story?

Gary Falcetano (25:53):

We'll have to see how that plays out. So let's get to some more questions. I had to put this one in because I'd love the quote. My infectious disease specialist had never heard of Alpha-Gal, and we know from the morbidity mortality weekly report that came out in, I believe it was 2023 in the summer of 2023, they identified a 42% of clinicians in their survey had never heard of the syndrome. So I think it's not unexpected that even several years ago there were a lot of people, even healthcare providers who really were unaware. But then I guess when this patient went to their food aller specialist, I assume an allergist, they called it the media Media darling of the century. So I guess what are your thoughts on that? Again, I think we talked about a little bit about how common that MMWR report said estimated 450,000 people in the US are potentially affected, but what are your thoughts?

Dr. Scott Cummins (26:49):

There's several points in there. To me, one of the most important is that we still have a lot of work to do raising awareness, and maybe in some places the allergists are completely fluent in AlphaGo syndrome, but I think across the US that may not necessarily be true, and if the allergists don't know about it, it's really hard to believe that it's permeated all the other subspecialties. So I'm not at all surprised that an infectious disease specialists might say, I've never even heard of that, because it isn't in medical textbooks, it's still fairly new, and I think we're all learning how do you change medical knowledge and how do you get the word out to folks? So again, this is a perfect use of what we're doing today. We still have a lot of work to do. I do think that there is probably a point that in some ways the media may like AlphaGo syndrome because it's different and it changes the way we think about food allergy.

Dr. Scott Cummins (27:51):

It also unfortunately demonstrates that just because you've reached your teenage years and you tolerate a whole class of foods, that tolerance can change. And that was a big paradigm shift in how we think about food allergy. So the idea that a tick bite can somehow break your tolerance to beef, pork, lamb, yeah, that gets your attention. So I think the point is well taken, but we still need to keep talking about it. And it is the common question, how common is it? That's a difficult answer because it matters where you live, where we are, where I am in Chapel Hill, gosh, it's really common. If you live in Denver, it's probably not common at all. So the geography is a big influencer there, and it gets back to a couple of the maps that we've shown in terms of how many years someone might be symptomatic.

Dr. Scott Cummins (28:46):

In general, I think this allergy almost likes to go away, meaning we see the Alpha-Gal IgE response decline almost naturally over a period of years. The problem is if you're someone who's an outdoorsy person and you end up with a GS because you like to hike or bike or hunt, and those are things you still do, you may get more tick bites and that's going to keep the allergy around. So in general, I tell patients it's probably a three to five year time horizon for this to go away, but if you get more tick bites, then you're probably going to be symptomatic for longer.

Gary Falcetano (29:26):

And we've seen studies where after each tick bite, the levels of AlphaGo sensitization dramatically rises again if it's been falling off. I think that's a really good point, and that actually brings us to the next question. When we talk about, you already discussed this came from a clinician and it was how common we discussed that, but what about modifiable versus non-modifiable risk factors? So I think modifiable, you were just talking about being an outdoor person, having greater exposure to ticks, but there are some non-modifiable risk factors are well or protective factors that have been kind of thrown around thinking specifically around the B blood group type patients. Right?

Dr. Scott Cummins (30:08):

And the background there for folks is that Alpha G as a true kind of carbohydrate, the galactose alpha one three galactose moiety is present in B blood group. It's just that there is another sugar that prevents it from being the traditional alpha G moiety, if you will. So there's an extra sugar there so that it doesn't really fully look just like Alpha G and b blood group has that. So, and when we look across our population groups and cohorts, we find that patients who are B blood type or ab blood type, their underrepresented, their percentage in the general population is greater than what we see amongst the AlphaGo allergic patients. So they're not a hundred percent protected. They can still get a GS, I don't want that to be a miscommunicated. They can absolutely get it. It just seems like their chances of getting it are less.

Dr. Scott Cummins (31:11):

And the other thing that we hear a fair amount about is this idea that if I go into the woods with my spouse, he or she would get all of the mosquito bites or ant bites or tick bites, and I don't think we fully understand what that is, and that's probably a non-modifiable risk factor that we're working on. What is it about some hosts that perhaps make them more likely to develop this? I think the other thing that I wanted to say about the risk in the general population is we recognize that this is a deficit in the research and there are multiple different ways that we're trying to get at it. And I think in the coming years we will have hopefully good data from a large national cohort to try to help establish what the general population kind of risk is of having Alpha-Gal IgE.

Gary Falcetano (32:11):

Thanks. Yeah. So the next question, I think we've covered already around theories, but do you have anything to add there or not so much why it's increasing, but maybe how we can as a medical establishment and how we can look to decrease?

Dr. Scott Cummins (32:27):

Yeah, I think on the decrease side, as you said sort of on the medical establishment side, what are the pharmacologic or medical interventions that perhaps we currently have? Can we repurpose some medicines that we have that might be able to cure or prevent a GS? There's probably some ideas there, but then I think the other side of this is the tick side, so what can we do to create a way that the deer perhaps are less likely to have and carry hundreds of tick? So I think deer population and different interventions there perhaps could lead to how we can really decrease the risk of a GS.

Gary Falcetano (33:12):

Yeah, almost from a population health perspective. And then finally, I guess, well actually we have two more questions on this slide, but this was interesting because initially the research around alpha gout patients, we saw a lot of them were not really atopic, they didn't have other allergies, but that's now changing as well.

Dr. Scott Cummins (33:31):

I think in general what we find is that when we look at our cohorts, there's this almost like a 50 50 split, meaning 50% of patients will say that they have a two P or other allergic diseases, and then the other half will say, look, I would have no reason to come to an allergist before I got this. I don't have seasonal allergies, I don't have eczema, asthma, et cetera. And this is different mind you than the traditional food allergy paradigm where we talk about the atopic march for babies that have eczema and progress. The tick bites seem like they can break that whole paradigm. So you could really live four or five or six decades with no allergic disease and all of a sudden develop AlphaGo syndrome.

Gary Falcetano (34:20):

You mentioned the atopic march, and I think what we're understanding now is the disruption with the atopic march often starting with atopic dermatitis or eczema skin issues, and we know that can lead then to other allergy like food allergy next, and we think it's because of some sensitization through the skin. Does that lead into why we think Alpha Gal is such a sensitizer because it's being injected or induced through the skin?

Dr. Scott Cummins (34:49):

Yeah, it is a fascinating point and I think you hit the nail on the head, which is we know that going through the skin, if you will, is really a fantastic way to make an allergic response. The IgE class of antibody is linked to that skin barrier disruption. So in that scenario or paradigm, the tick portion of this becomes sort of scientifically satisfying, I guess, because you don't then start to have to feel like, well, I've got to create some other reason why people are getting a GS. The tick bite story is sufficient based on what we think the role of the skin is in promoting allergic disease.

Gary Falcetano (35:33):

We haven't, and we will talk in just a minute about other causes besides foods of AlphaGo symptoms, but are symptoms from ingestion of foods always delayed or do we sometimes see immediate symptoms?

Dr. Scott Cummins (35:49):

They are largely delayed. There certainly can be instances where someone reacts faster than two hours, and that tends to be the co-factors that we'll talk about. So no, it's not a hard and fast always, but I would certainly say overwhelmingly symptoms from ingestion in particular are delayed, are delayed.

Gary Falcetano (36:12):

And I think we've already talked about that. So let's move on. When we think about the symptoms in both adults and in children, again, when you were first working on this, I don't think we really saw much of this at all in shelter. We thought you had to be kind of an older gentleman who spent a lot of time in the woods in order to contract this, and that's just not the case when we actually start looking at the demographics currently. So yeah, maybe speak to that. And also, you mentioned all these symptoms, and again, they're not necessarily progression. They can be isolated GI or isolated urticaria and certainly progress to anaphylaxis. But discuss this a little bit, would you?

Dr. Scott Cummins (36:54):

You're absolutely correct. When we initially were identifying Alpha-Gal syndrome, we really had no awareness that kiddos could be affected. And as you indicated, we thought this was really an adult based allergy. And so there's two misconceptions that we had early on, and that was one of 'em. Subsequent publications, totally detailed AlphaGo Syndrome in kiddos, it looks and presents in many ways exactly like it does in adults. They get hives and GI distress, they get anaphylaxis, they need EpiPens and autoinjectors, epinephrine of whatever variety, and they end up in the emergency department. It appears in children basically the same as it does in adults clinically, they have histories of tick bites. The other misconception we had was we were not aware of this isolated gastrointestinal presentation, which has really come to light in the past several years, where those patients don't have itchy palms or hives or angioedema. They get basically terrible abdominal pain, cramping, distress, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and so it may not look at all like a food allergy. In fact, it probably looks more like food poisoning. And so we've learned for that part of the symptom breakdown of this too. But yes, those were two big misconceptions that we've now sort of expanded the understanding of AlphaGo syndrome.

Gary Falcetano (38:36):

And I think our colleagues on the gastroenterological space have come out with some clinical guidance on having a high index of suspicion when you do have these unexplained GI symptoms including symptoms like from irritable bowel syndrome.

Dr. Scott Cummins (38:49):

Yeah, absolutely. And in some, again, gets back to the geography part of this right there in some locales, the GI docs are incredibly good at picking this up.

Gary Falcetano (39:00):

So I've been waiting to get to this slide because we have been pretty much ignoring other than food causes of Alpha Gal syndrome. And we know that initially some of the initial work that was done went around Cetuximab infusions, an anti-cancer drug where people were reacting to their first initial infusion, which is not typical for an allergic reaction to a medication. And that kind of helped in the whole identification of Alpha Gal being the causative factor. But let's start on the food side of things and about the differences in the concentrations of alpha gallon, the various foods.

Dr. Scott Cummins (39:36):

When we think about the foods, probably the biggest, the foods that carry the most risk for reaction are organ meats, I believe. And then below, if you will, just like a rung down on the ladder would be fatty meats. So there really are differences in clinical symptoms based on the characteristics of the meat that one eats. So

Gary Falcetano (40:02):

Have the filet and not the ribeye is what you're

Dr. Scott Cummins (40:04):

Saying, and a weird twist of fate, right? The filet is actually better for you. So the fattier meats are associated more consistently with reactions and more severe reactions. And then after the meats we get to kind of the dairy part of it. Again, ice cream pizza, the higher fat dairy foods are associated more consistently with reactions and symptoms. And then beyond that, you get to gelatin. Not everyone is bothered by gelatin. It's important to say that even though this hierarchy almost exists, at some point people may say, look, I can drink cow's milk just fine. And that's okay. But when we think about the risk, it really seems to be those organ meats at the top of the list and then at the bottom, the very kind of low fat lean things, and then gelatin beyond that.

Gary Falcetano (40:59):

So when we move over to medications and biologics, this can be really scary. People that have a diagnosed AlphaGo syndrome, they see this list and it can be a little overwhelming, but put this into perspective a little bit for us.

Dr. Scott Cummins (41:14):

Yeah, I think a couple of things here. One is the, as you mentioned, the Cetuximab story, which is fascinating but lengthy. We'll sort of skip that for today. But the important point about Cetuximab is it's an infusion and those reactions happen very fast. So there really is the delay has to related to ingestion and processing. The other part of this, the medication story, often people are okay with capsules and gel caps, that kind of thing. Heparin at low doses is largely fine for many patients, but as you mentioned, it's the unknown portion of that. Could I react to an anti-venom? And then having to make that decision in the moment of do I take the anti-venom or do I worry about the reaction? Almost universally, I encourage people to take the anti-venom and we can deal with the allergic symptoms if they happen. But there's a lot that we're working on here that isn't fully known. Heart valves for example. Is there a risk of that valve having early deterioration because you have alpha-gal epitopes structures on the pig or cow heart valve, and if you're allergic to that, does that affect it? We don't know. We're kind of in equipoise at the moment about that portion. Many of these things are surmountable, meaning MMR vaccine. There is one offered that is alpha gal safe, that is a shingles vaccine hinrich that doesn't have Alpha G. So it's an important discussion and one where we're looking to add more data to it as well.

Gary Falcetano (42:57):

And I think it's really important for these individualized discussions to take place between a very knowledgeable clinician and the patient because it is such an individualized kind of response. But I do want to, before we get away from this slide, talk about co-factors. We've talked about this in some previous fair webinars, the importance of co-factors and how they can alter someone's response to something they're sensitized to. But it seems to be especially important in Alpha-Gal syndrome and especially alcohol, correct?

Dr. Scott Cummins (43:26):

Correct. The co-factors are a huge part of predicting more severe reactions and more consistent reactions too, particularly in our alpha-gal allergic adults and very active children. So alcohol is a bad actor, and exercise we find are probably the two most common causes of people having more severe symptoms. And we even find some patients that their reactions are almost dependent, if you will, upon ingestion of alcohol or recent exercise, meaning within two to four hours of ingestion.

Gary Falcetano (44:05):

So going back to that stake, the stake without the red wine, it's okay for some patients, glass of red wine puts them over.

Dr. Scott Cummins (44:14):

It could be safer in some way to think about it that way. And in many ways, the worst case scenario is an exercise, a period of exercise followed by the meal that may contain alcohol. Those traditionally in the AlphaGo syndrome space lead to stories that are documented with severe reactions. Recent tick bites seem like their role is to probably push the AlphaGo specific IgE, but in some ways that probably sensitizes or reinvigorates the allergic response as well.

Gary Falcetano (44:45):

So let's get to our final set of questions, and we just have a few here. So without further tick bites, I think you mentioned this already, we tend to see alpha-gal levels decline and then often patients are once again able to tolerate mammalian meats. I think you said three to five years, but that's again, very individualized. Correct.

Dr. Scott Cummins (45:05):

It is individualized three to five years sort of the broad stroke that for a typical patient without additional bites, we usually could see resolution in that time period. They can fully add things back to their diet. Their risk is not done, it's not a cure. It's resolved and future bites could in fact bring it back, and we've seen that as well.

Gary Falcetano (45:27):

Okay. And then what about food labels? We mentioned there's a whole kind of spectrum of foods that potentially contain Alpha Gal. What are some advice for patients on this?

Dr. Scott Cummins (45:37):

Really tough to read food labels related to Alpha Gal syndrome, particularly if you're quite sensitive. Fortunately, I think there's a bill that we hope Congress will pass related to food labeling. It's probably the number 10 allergen in the country, and it's just a challenge because the labels aren't made for mammal. In fact, there's this buzz phrase called natural flavors that food manufacturers may put on the label, which often means they've added beef or pork flavor or fat to the product. So it is just incredibly difficult in many instances to be quite confident about what's on the label.

Gary Falcetano (46:15):

I did mean to ask you actually about that. We had the big eight food groups that were responsible for 90% of food allergies that in the last several years went to the big nine with the addition of sesame. So what you're saying is Alpha G is right behind SESAME then and being the 10th.

Dr. Scott Cummins (46:32):

Yeah, unfortunately, I think that's true based on the CDC projections of probably 450, close to half a million people in the US alone affected by A GS. So at that level it would probably make a GS the 10th most common, unfortunately.

Gary Falcetano (46:51):

And I would say it's that list that then gets the FDA's attention for required labeling, correct. That's where the threshold is, right?

Dr. Scott Cummins (47:00):

I think so. My understanding is it's a congressional issue for labeling. Okay.

Gary Falcetano (47:05):

Okay. So I think you mentioned there's been some research into other treatments besides avoidance, but we're not there yet, are we? Don't have any,

Dr. Scott Cummins (47:13):

We're not, not currently there for, I would say like an Alpha GAL specific treatment, certainly the FDA approval of Omalizumab, which is Xolair for food allergy last February has been really important and significant advance for patients with all food allergies. But certainly we've used Xolair with excellent success in the Alpha-Gal syndrome patient as well.

Gary Falcetano (47:40):

We've seen there are some kind of trials out there with some other techniques, but I think they're pretty early stage.

Dr. Scott Cummins (47:48):

Yeah, there early. Gosh, we'd love to have a venom immunotherapy approach where we could give people shots related to their tick saliva exposure perhaps, but we're just quite there yet.

Gary Falcetano (48:00):

What about relationships with other food allergies and autoimmune diseases? Are we seeing any connections there?

Dr. Scott Cummins (48:07):

No real documented connections with other autoimmune diseases. To my knowledge. I think AlphaGo Syndrome because of that, we're talking about the 50 50 A two P non A two P group. We haven't really found as much with the other food allergies. In some ways, AlphaGo syndrome seems to exist outside of that traditional atopic march.

Gary Falcetano (48:30):

Gotcha. And then this may not be able to be answered quickly, and we're running out of time because we've had so many great questions already. But is there an association, do you think, between mast cell activation syndrome, postural orthostatic syndrome, and a GS?

Dr. Scott Cummins (48:44):

Yeah, I think this probably could be a full hour as well, but my short answer, I do think there's something about the tick bite that may activate mast cells, and so not uncommon that we might think about that too. In a venom B wasp sting allergy, scorpion bite sting,

Gary Falcetano (49:06):

We have seen increased levels of tryptase in patients that are having more severe alpha-gal reactions, right? So we don't know.

Dr. Scott Cummins (49:13):

Yeah, absolutely. The reactions to a GS when we've done it in a controlled way and fed people allergen, their tryptase levels do go up, and I think there's reason to think there could be, or there is overlap, but certainly needs more recert

Gary Falcetano (49:29):

And potentially more higher prevalence in patients with mast cell activation syndrome or mastocytosis or something like that as well.

Dr. Scott Cummins (49:36):

Yeah, you could certainly see where if you have a mast cell related issue, maybe your response to tick bites then predisposes you to develop an IgE response to AlphaGo.

Gary Falcetano (49:47):

Yeah, for sure. So quickly, especially for the clinicians in the audience, there's been some thoughts around, just because we have a sensitization, we know that doesn't equate to clinical allergy, but are there levels that are typically more likely to be true alpha gal rather than a sensitization without clinical symptoms? I think you said as we get more experience, our thoughts are changing a little bit around this.

Dr. Scott Cummins (50:12):

We've seen really that you can have a fairly low level to AlphaGo IgE and be extremely allergic, very sensitive, where cross-contamination bothers you, et cetera. I don't know that I use the 2% perhaps as much as maybe others might, but really paying attention to that clinical history. Are you positive or not?

Luke Lemons (50:35):

Luke here popping in what Dr. Cummins means by that 2% comment is related to this slide. Looking at results, so on this slide, there is IgE results for beef, pork, lamb, alpha gal tryptase in total IgE. Now looking specifically at alpha-gal, if the AlphaGo levels are greater than or equal to two kilo units per liter, or if the Alpha-gal IgE is greater than or equal to 2% of the total IgE than an AlphaGo syndrome, diagnosis is likely

Gary Falcetano (51:12):

Even a low level is significant regardless of the total IgE. But sometimes, I guess if the total IgE is low and you have a higher percentage, it kind of pushes you a little bit more towards the diagnosis.

Dr. Scott Cummins (51:23):

It may indicate that you have less other IgE that would interfere perhaps in those scenarios. So you're maybe even more likely to react with a low total IgE and a positive alpha gal specific IgE. That

Luke Lemons (51:40):

Brings us to the end of this fair webinar. I hope you enjoyed listening and gained some great clinical insights into AlphaGo syndrome. The link in the description of this video will contain a link to go visit this webinar if you wanted to watch it, as well as some additional resources that you can use when thinking of diagnosing patients with AlphaGo or management considerations. Thank you again for listening to ImmunoCAST.

Announcer:

ImmunoCAST is brought to you by Thermo Fisher Scientific creators of ImmunoCAP Specific IgE Diagnostics and Phadia Laboratory Systems. For more information on allergies and specific IgE testing, please visit ThermoFisher.com/immunocast. Specific IGE testing is an aid to healthcare providers in the diagnosis of allergy and cannot alone diagnose a clinical allergy. Clinical history alongside specific IgE testing is needed to diagnose a clinical allergy. The content of this podcast is not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as or substitute, professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Any medical questions pertaining to one's own health should be discussed with a healthcare provider.

- Carpenter A, Drexler NA, McCormick DW, et al. Health Care Provider Knowledge Regarding Alpha-gal Syndrome — United States, March–May 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023;72:809–814.

Legal manufacturer: Phadia AB.

Before you proceed ...

We noticed you may be visiting a version of our website that doesn’t match your current location. Would you like to view content based on your region?

Talk with us

Interested in utilizing our solutions in your laboratory or healthcare practice?

This form is dedicated to healthcare and laboratory professionals who work within medical laboratories, private practices, health systems, and the like.

By clicking "continue with form" you are confirming that you work within a healthcare or laboratory space.

Not a lab professional or clinician but interested in diagnostic testing for allergies?

Visit Allergy InsiderChoose your preferred language

Please note: By selecting a different language, you are choosing to view another site. Product availability and indications may vary from what is approved in your region.