Episode 033

Dust mites to dinner plates: Unexpected insect allergies in clinical practice

-

Summary

-

Episode Resources

-

Transcript

-

Related Episodes

Episode summary

Did you know the average person unknowingly consumes about 2 pounds of insects or insect parts annually? This startling fact underscores the ubiquitous presence of insects in our environment and diet, presenting unique challenges in allergy diagnosis and patient management. This episode of ImmunoCAST explores the multifaceted world of insect-related allergies, moving beyond common respiratory or stinging triggers to uncover lesser-known presentations. We explore the "Pancake Syndrome" and its link to dust mites, discuss the cross-reactivity between dust mites and shellfish, and examine the allergenic potential of insect-derived food additives. By understanding these complex interactions, clinicians can enhance their diagnostic acumen and provide more comprehensive care for patients with suspected insect allergies.

Episode resources

Find the resources mentioned in this episode

Lab Ordering Guide

Looking for allergy diagnostic codes from the labs you already use?

Episode transcript

Time stamps

1:30 - Conventional insect allergies (respiratory and stinging insects)

3:27 - Introduction to less common insect allergy presentations

4:18 - Insects as food sources and nutritional benefits

5:03 - Insect contamination in food

6:42 - Pancake Syndrome (Oral Mite Anaphylaxis)

8:51 - Dust mites, tropomyosin, and cross-reactivity with shellfish

13:40 - Clinical implications of dust mite and shellfish cross-reactivity

14:26 - Carmine red dye and potential allergic reactions

17:53 - Recap and importance of thorough allergy history

19:29 - Conclusion and resources

Transcript:

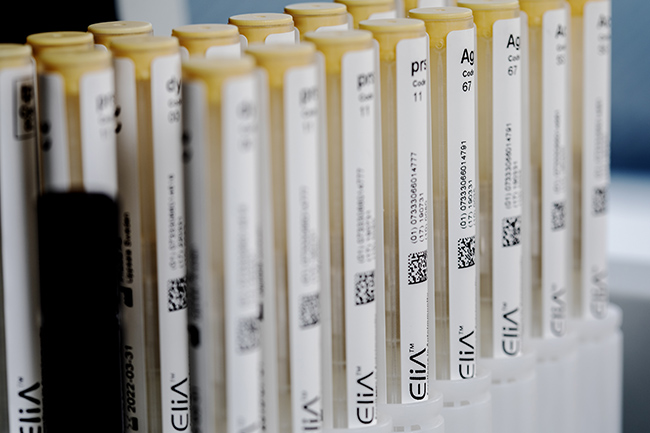

IgE diagnostics and Phadia Laboratory Systems.

Gary Falcetano:

I'm Gary Falcetano, a licensed and board-certified PA with over 12 years experience in allergy and immunology.

Luke Lemons:

And I'm Luke Lemons, with over six years experience writing for healthcare providers and educating on allergies. You're listening to ImmunoCAST, your source for medically and scientifically-backed allergy insights. What do cockroaches, dust mites, and shrimp have to do with pancakes?

Gary Falcetano:

Oh, it does not sound like a very good pancake mix.

Luke Lemons:

No. No, it doesn't. We're going to go into that a little bit more later on. But to give everyone listening a hint, we're going to be talking about bug or insect allergies today. But before we dive into some of the lesser-known ways, pancakes, the insects may come in contact with patients and cause reactions. We'd be remiss to not mention some of the more conventional allergies that insects may cause.

Gary Falcetano:

Yeah, absolutely. So, I think when we think about insects, and how they affect our health and allergy, we typically think of respiratory issues. We think of rhinitis, and asthma, and how exposure to cockroach and dust mites are such big drivers. When you're sensitized to cockroaches and dust mites, how much that actually drives our respiratory allergies. But there's more to bug allergies than just that.

Luke Lemons:

Yeah. And I think that most of the providers listening, when they think of insect allergies, they might go straight towards bees or vespids.

Gary Falcetano:

Yeah, that's right.

Luke Lemons:

And that's common. But some providers may not know actually that a lot of those severe reactions to bees and vespid stings and their venom are actually under-reported by patients. And also, that the venom immunotherapy in which you may refer to an allergist, if you do have a patient who had a severe reaction, it's very successful form of therapy.

Gary Falcetano:

We've talked about this in previous episodes. We had Dr. Golden with us on our Anaphylaxis and Stinging Insects episode back in episode 27. I think we did one ourselves, episode 13, on stinging insects. And it really is. It's vital that providers have that index of suspicion. Anytime we're seeing patients, part of that initial history should be have you ever had a systemic reaction to an insect sting, because people don't report it.

Luke Lemons:

And I'm glad you mentioned the past episodes that we've done, because we've talked about insects in the past. And we've definitely talked about them, but from a respiratory point of view with dust mites and asthma. We've definitely talked about them when it comes to stinging insect venom. And then also, alpha-gal syndrome, which isn't necessarily an allergy to an insect, but it's an allergy that's caused by a tick bite.

Gary Falcetano:

The tick is the vector for the transmission. So, people that are bitten by certain ticks, and we used to think these were specifically the lone star tick, develop a sensitization to alpha-gal and then develop what is known as a delayed red meat allergy. But it's not just the lone star tick anymore, right, Luke?

Luke Lemons:

This is probably a topic for another episode, but there's new ticks out there. New ticks are dropping that are causing alpha-gal. So, the black-legged dog or wood tick is common in Maine. And then the western black-legged tick is common in Washington.

Gary Falcetano:

And we just saw a couple of reports coming out of the CDC of case reports from both of those areas, implicating those ticks. So, yeah, we'll have more on that I'm sure in future episodes. But the alpha-gal story is far from over.

Luke Lemons:

If you're interested in learning more about alpha-gal, episode 11 and episode 29, Gary and I discussed that. But outside of bites, stings, and inhalation, how else may patients react to insects? And the answer that I know we don't really want to think about is... Well, why don't you say, Gary?

Gary Falcetano:

Well, so entomophagy or eating them?

Luke Lemons:

Yes. Yes. So, insects are closer to food than we think. Some people eat insects on purpose and some people eat insects because of contamination. And actually, when it comes to being on purpose, it's really common in Asian and African countries, but it's gaining popularity in Europe.

Gary Falcetano:

It is. I mean, as we see our global population continues to expand, this is one of the areas that has been really looked at as a potential new food source to be able to feed all of the people that we're going to have on the planet.

Luke Lemons:

Yeah. And when somebody does eat insects, they are actually getting some pretty good nutrients. Polyunsaturated fatty acids, essential amino acids, micronutrients, and other types of protein.

Gary Falcetano:

Yeah. Many of the nutrients that we need to survive can be supplied by insects.

Luke Lemons:

Which may be why in 2021, the EU approved mealworms and locusts as safe for human consumption. And actually, recently, more recently, Italy has started using cricket flour, which is, as you can guess, flour made from crickets and said to taste like pumpkin seeds, hazelnuts, and a little bit like shrimp.

Gary Falcetano:

Just a little bit like shrimp. There's also other positive aspects. The general thinking is there's less environmental impact from using insects as food than occurs when we breed livestock.

Luke Lemons:

Yeah. And I think that these are all reasons, that in the future that may be more and more common, that we see patients eating insects intentionally. But where it is now, at least in America, most patients are exposed to ingesting insects due to contamination. And here's a little disgusting fact for all of you listening. The average American eats about two pounds of insects or insect parts in a year. And that's from the Center of Invasive Species Research.

Gary Falcetano:

Not on purpose.

Luke Lemons:

Not on purpose. This is all contamination, so two pounds.

Gary Falcetano:

And that's from the Center for Invasive Species Research right out of the University of California?

Luke Lemons:

Yes. Yes. And it's not just this center that has done this research on insects and food. The FDA actually has a food defect levels handbook where they outline that peanut butter and other foods, well, peanut butter specifically, they will only allow an average of 30 or more insect fragments per 100 grams. Anything more than that, it's not safe.

Gary Falcetano:

Per 100 grams. So, 100 grams is, I don't know, three and a half ounces in that 26 ounce jar of peanut butter that's sitting in my closet? What are we talking about there? A lot of insect fragments that the FDA literally allows, right?

Luke Lemons:

You're going to have 25 insect fragments per 3.5 ounces.

Gary Falcetano:

And that's fine?

Luke Lemons:

But 30 is where we draw the line. And actually hops, for anyone out there who drinks beer, the average that they'll cut off before its unsafe for consumption is 2,500 aphids per 10 grams.

Gary Falcetano:

10 grams is not a lot of hops. I got to think, even though we're making beer out of it, that's a lot of aphids.

Luke Lemons:

So, bugs, they're in our food. It's a brutal truth. But what does this have to do with allergies?

Gary Falcetano:

When we think about going back to those respiratory allergies with dust mites, that's not the only way we're exposed to dust mites. And that's where it comes, brings us back to what you mentioned earlier, right, Luke? This pancake syndrome or otherwise known as oral mite anaphylaxis. Tell us a little bit about that.

Luke Lemons:

Like the name oral mite anaphylaxis suggests, it's from ingesting dust mites or storage mites that are commonly found in flour. So, this is flour that is used for pizza, pasta, cornmeal, cake, et cetera. It's really more common in tropical and subtropical environments. But yes, there's dust mites in the flour. The wheat flour is contaminated with dust mites.

Gary Falcetano:

And people actually develop or exhibit food allergy symptoms after ingesting the dust mites that are contained in this flour. And I guess, mostly if the flour is not well-sealed or it's exposed to a lot of moisture, we know we've talked about how dust mites require moisture to live. So, I assume that goes hand-in-hand with them being in the flour in the tropical areas.

Luke Lemons:

Yeah. And they actually recommend that to store wheat flour in low temperatures or in the refrigerator, if this is something that may affect you.

Gary Falcetano:

I'm in Florida, so it probably would affect me.

Luke Lemons:

Oh, yeah, yeah. Oh, definitely. But it's a really interesting syndrome. And so, it technically is a dust mite allergy, though. The patient is eating flour that has these mites in it. So, what does that mean though for patients who have a respiratory dust mite allergy, if they have flour that has mites in it?

Gary Falcetano:

Yeah. I think because we know to diagnose this oral mite anaphylaxis, we need to do, like always, a history that equates ingestion of the suspected food with symptoms. So, once we've equated ingestion of flour, we need to rule out wheat allergy, as opposed to dust mite allergy that's in the wheat. So, definitely testing for wheat allergy is important. But also, then looking at if someone has respiratory symptoms, we should probably be testing them for specific IgE to dust mites, to see if we can make that connection to pancake syndrome. Again, this isn't super common, but it does happen. And there's been multiple cases reported throughout the US.

Luke Lemons:

Yeah. And this is one of those rare syndromes where we have an overlap between respiratory and food allergies, where we have the respiratory allergy with dust mite. And then if you eat the dust mite, you might experience some food allergy symptoms similar to pollen food allergy symptom, or similar to pollen food allergy syndrome, which is a cross reaction between pollen, and some fruits and vegetables. But what exactly, Gary, in the dust mite is causing this reaction? And why can they eat baked pizza, baked cake?

Gary Falcetano:

No, they can't, actually. So, major proteins that are associated with this oral mite anaphylaxis are thought to be the tropomyosins. And the tropomyosins are heat stable, heat-resistant proteins that are present in both uncooked and cooked versions of the foods.

Luke Lemons:

Yeah. And so, you can't bake away the dust mites or the tropomyosin.

Gary Falcetano:

But there's also something interesting about this pancake syndrome. There's even a subset of patients who have pancake syndrome, and it's related to exercise. So, remember back in our... I'm trying to remember the episode.

Luke Lemons:

Oh, our Olympic episode, Olympic athletes.

Gary Falcetano:

Yes, right. It was our Olympic athletes and how exercise can impact allergy. And we talked about the syndrome wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis. Well, this is another wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis, except it's because of the dust mites. So, there's a dust mite anaphylaxis pancake syndrome that's related to exercise as well. So, a lot of interrelationships here.

Luke Lemons:

We keep saying dust mites, but it's really that protein, the tropomyosin that is causing that reaction. And tropomyosin, for those providers out there who may not know, it is a muscle contraction protein. And it's actually found throughout life.

Gary Falcetano:

Yeah. All eukaryotes, so from humans to dust mites, to everything in between, including shellfish, where we see those tropomyosins that are very cross reactive with the dust mite proteins.

Luke Lemons:

You're getting at what we were hinting at with the shrimp earlier, is in shellfish meat, tropomyosin is actually an abundant protein. And nearly 20% of the total protein content in shellfish is tropomyosin. And when it comes to allergic sensitization to tropomyosin, it's seen in up to 80% of shellfish-allergic individuals.

Gary Falcetano:

So, let me just repeat that, Luke. So, when people have an individual, a patient has a shellfish allergy, up to 80% of the time it's the tropomyosin that's actually driving that allergy. And we also know that one in 10 patients who are sensitized to dust mites and have a dust mite allergy will also have a shellfish or specifically a shrimp allergy, correct?

Luke Lemons:

Yeah. And again, this is because that tropomyosin found in the dust mite is very similar to the tropomyosin found in the shrimp. So, out of the 10 patients that you have that come into your office who have a house dust mite allergy, one of those patients may also react with shrimp.

Gary Falcetano:

Exactly. Which is why doing a thorough allergy assessment and history is very important for patients who have both respiratory and food allergy-like complaints.

Luke Lemons:

So, you may have a patient that you've clinically diagnosed using clinical history and specific IgE testing as having a dust mite allergy. And I know that in a perfect world, people are exposed to thing... or an imperfect world, people are exposed to things that they may not know. But if we imagine a patient who has never touched a shrimp in their life, if they have been exposed to house dust mites and develop an allergy, even though they haven't been sensitized to the shrimp directly, through ingestion-

Gary Falcetano:

Through ingestion of the shrimp.

Luke Lemons:

... there is a chance that the first time that they do have shrimp, they may have some sort of reaction because of this cross-reactivity.

Gary Falcetano:

Yeah, that's right. I mean, one of the truths in allergy is you have to be sensitized, develop IgE antibodies and then re-expose in order to have symptoms. But there are multiple ways to be sensitized. And in this case, they could be sensitized by a dust mite allergy that then translates into having a food allergy to shrimp or other shellfish.

Luke Lemons:

Yeah. And it's not just dust mites, too. Cockroaches as well contain this tropomyosin that is similar to dust mites and shellfish. So, I mean, in a way, shrimps, they're grouped in with the bugs in a way when we think about allergy.

Gary Falcetano:

Well, they are. They're actually in that arthropod family. So, dust mites, and the shrimp, and lobster, they're all in that arthropod family. So, they share a lot of similarities, including tropomyosins.

Luke Lemons:

And so, patients out there who do have dust mite allergies, who've been diagnosed, if they've also been talking about having symptoms to shrimp, of course, that's a clinical history, so evaluate them for a shrimp allergy. But also, it's good to explain to these patients that as gross as it may sound, there may be some cross-reactivity there in their immune system reacting to both shrimp and the dust mites.

Gary Falcetano:

The other kind of hypothetical thing to think about is that if someone does have a dust mite allergy, let's address that. Let's actually do some mitigation interventions to reduce their exposure to dust mite, improving hopefully their respiratory symptoms, but potentially also lowering their threshold if they have any type of symptoms with shrimp as well.

Luke Lemons:

Yeah. 100%, Gary. And this isn't the only way in which bugs may enter our diet. Whether it's through contamination and unknowingly eating an insect, there's also food dyes which are more intentionally put into foods. Specifically, we see carmine red, which is made from a beetle-like insect. And you may see it named on packaging as E120 or natural red dye four.

Gary Falcetano:

And it's not just in foods, but it's also in cosmetics, things like lipsticks. And it's from this, as you said, beetle-like insect called the cochineal insect. And this is a small parasitic insect that's actually found on the pads of the prickly pear cacti. So, predominantly grown in Mexico, Chile, Argentina, the Canary Islands. It's a big source of colorants for hundreds of years, actually, fabric dyes. But more recently, being used increasingly as a food dye, as a natural alternative to some of the artificial red dyes.

Luke Lemons:

Yeah. And when we hear the word natural, let's really hone in on that natural, because it's made of beetles. And beetles are natural. You mentioned those other countries, but Peru is actually the largest producer of this dye.

Gary Falcetano:

That's right. That's right. Yeah. I did miss Peru, didn't I?

Luke Lemons:

Yeah. It's just a very interesting concept to take these beetle-like insects and turn them into this red dye. In fact, you need about 70,000 of these bugs to extract just a pound of the dye. I think kind of like a red that you would see on a lollipop or in sugary-

Gary Falcetano:

Some type of sugary drink, right?

Luke Lemons:

Yeah, exactly. But it's also, we mentioned earlier with why people may start eating bugs. The reason that some companies may use carmine is because it's more sustainable. It's a little better for the environment because it is natural. Maybe a little gross to think about. But because it's organic and natural, it's possible that somebody may develop an allergy to it.

Gary Falcetano:

Yeah. And there is testing for this, Luke. So, there is specific IgE testing for carmine red. So, if there is... based upon history, there's a suspicion that a patient may have symptoms when exposed to it, we can get a specific IgE test to help confirm that.

Luke Lemons:

And just to be clear, when we talk about this dye made from insects, we're not necessarily talking about reactions to other dyes that may be synthetic or artificial. In fact, tartrazine is a synthetic dye that you hear a lot about. People may say that they have an allergy. They may come in and say, "Well, listen, Clinician Smith, I have a reaction to tartrazine dye." Well, that's actually-

Gary Falcetano:

Yeah, that's a yellow dye, right?

Luke Lemons:

Yeah, it's a yellow dye. But it's actually synthetic, so it's more of an intolerance. So, again, when we talk about allergies, we're talking about IgE-mediated reactions, which is why IgE testing is such an important step in diagnosing an allergy alongside clinical history.

Gary Falcetano:

Right. And there really isn't any tests per se for these reactions to synthetic dyes. But as I mentioned, we do have testing for carmine red, which is a protein from the cochineal insect.

Luke Lemons:

Yeah. And so, when we think about bugs and insects in our patients' lives, in the way that they may react, of course, we jump to respiratory triggers with cockroaches and dust mites. We jump to stinging insects, like bees and wasps or the vespids causing reactions. And then maybe alpha-gal with a tick bite and having a red meat allergy. But it's important to remember that there's a whole other facet to how insects may interact with a patient's immune system.

Gary Falcetano:

Exactly. Both by contamination of foods and purposeful ingestion of insects, especially as we move into the future as a new food source. Keeping these things in mind and knowing that when it comes to allergy, history is of utmost importance. We need to be comfortable with doing a very focused, thorough allergy history. And then when it is a suspected IgE-mediated allergy, basing our diagnosis on that history combined with specific IgE testing, to really help to rule out or confirm those food allergies or respiratory allergies for that matter.

Luke Lemons:

Exactly. And so, on this episode's specific page, which you can access via the link in the description, we'll have links to some of those other episodes that Gary and I shouted out in case you didn't have a pen and paper handy to write down those episode numbers. But we'll also have information on ordering specific IgE, as well as additional resources that can help you as you develop your allergy care and optimize patient outcomes. Thank you for listening to ImmunoCAST. And have some stacks of pancakes for Gary and I, if you weren't thinking about it already.

Gary Falcetano:

Exactly. And don't think about those two pounds of bugs that you're going to ingest this year. Thanks so much for listening.

Luke Lemons:

Thank you, everyone.

Gary Falcetano:

We'll see you next time.

Luke Lemons:

Bye.

- Sustainable, edible and nutritious – think about insects again!. HEALTH AND FOOD SAFETY - Sustainable, edible and nutritious – think about insects again! (n.d.). https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/sante/items/787829/en

- Entomophagy (eating insects). Center for Invasive Species Research. (2022, September 28). https://cisr.ucr.edu/entomophagy-eating-insects

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. "Food Defect Levels Handbook." Food and Drug Administration, https://www.fda.gov/food/current-good-manufacturing-practices-cgmps-food-and-dietary-supplements/food-defect-levels-handbook. Accessed April 2025

- De Marchi L, Wangorsch A, Zoccatelli G. Allergens from Edible Insects: Cross-reactivity and Effects of Processing. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2021 May 30;21(5):35.

- Sánchez-Borges M, Suárez-Chacon R, Capriles-Hulett A, Caballero-Fonseca F, Iraola V, Fernández-Caldas E. Pancake syndrome (oral mite anaphylaxis). World Allergy Organ J. 2009 May;2(5):91-6.

- Sandip D. Kamath, Tropomyosin: A cross-reactive invertebrate allergen, Editor(s): Scott H. Sicherer, Encyclopedia of Food Allergy (First Edition), Elsevier, 2024, Pages 310-319, ISBN 9780323960199,

- Rohrig, B. (n.d.). Eating with your eyes: The Chemistry of Food Colorings. American Chemical Society. https://www.acs.org/education/chemmatters/past-issues/2015-2016/october-2015/food-colorings.html

Legal manufacturer: Phadia AB.

Before you proceed ...

We noticed you may be visiting a version of our website that doesn’t match your current location. Would you like to view content based on your region?

Talk with us

Interested in utilizing our solutions in your laboratory or healthcare practice?

This form is dedicated to healthcare and laboratory professionals who work within medical laboratories, private practices, health systems, and the like.

By clicking "continue with form" you are confirming that you work within a healthcare or laboratory space.

Not a lab professional or clinician but interested in diagnostic testing for allergies?

Visit Allergy InsiderChoose your preferred language

Please note: By selecting a different language, you are choosing to view another site. Product availability and indications may vary from what is approved in your region.